Writing on Writing Materials (Part-1)

[1]

About 5,500 years

ago, ‘history’ began. In other words, Man developed writing system - a

marvellous technology which allowed him to record information, ideas and

discoveries. He was no longer needed to depend only on his memory. He had found

the way to visually represent his words in the form of signs. These ‘written’ words

could now be used for communication across long distances and, most

importantly, passed on to the future generation with unprecedented reliability.

The invention of writing system was, indisputably, one of the greatest achievements

of humanity.

[2]

To me, the very

process of writing is fascinating. However, what captivates me the most are the

tools or materials involved in this process. Through this series of blogs, I

intend to share whatever I know about the evolution of writing materials

throughout the course of history, in a concise manner. This particular blog

(i.e., part-1 of the series), is about the writing materials used in the

ancient region known as the Fertile Crescent and Europe until the medieval

period. My knowledge is rather scarce, and there is a lot more I have to learn

on this topic. Still, I sincerely hope that my content will entertain you.

[3]

Who started writing first? The Mesopotamians? Or the Egyptians? – I have heard that researchers often differ on this topic. As for me, I am a mere school student who knows too little to develop any opinion. Nevertheless, as far as the theme of this blog is concerned, I am going to start with the Mesopotamians, because their writing materials “feel more primitive” to me.

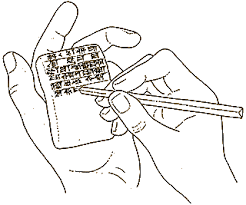

In ancient

Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq), the ‘instrument’ used for writing was nothing but

a simple stylus made from a cut piece of common reed (Phragmites australis),

something which grew abundantly in the region. The writing surface was clay,

acquired from the banks of the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, which was then formed

into a nice flat tablet. To write, one would take a clay tablet when it’s still

soft and press it with his or her stylus producing a wedge-shaped impression on the

surface. As a matter of fact, the wedge-shape of the signs, produced by a reed

stylus, was very much archetypical of the logo-syllabic script used by the

Mesopotamians which is hence named Cuneiform (‘cuneus’ meaning wedge in Latin).

Isn’t that interesting?

Now, let’s move to “the

land of the riverbank” – Egypt. The earliest writings found here were carved on

the walls of temples and monuments. The script was, off course, the famous

hieroglyphics, which actually derives from a Greek word meaning ‘sacred carving’.

So, we can say that the earliest writing tools of Egypt were a hammer and chisel.

However, hammer and chisel were not only writing tools; walls were not the only

writing surface; and the ‘sacred carving’ didn’t remain restricted to carving

only.

The Egyptians used reeds (probably calamus reed), cut to the length of about 6 inches. One end of the reed was soaked in water for a while to soften it, and then that end was chewed to separate its fibres. The piece of reed now had a brush-tip to write with! They made ink by burning oil or wood and mixing the obtained soot particles with water and gum. Other colours were produced using various minerals or compounds. I have also read somewhere about lead-based inks as well. The scribes loaded their reed brush with ink (or colour) to write hieroglyphics on surfaces such as wooden boards, fragment of limestones (and, obviously, stone walls) often to accompany beautiful paintings illustrating significant events. Other writing methods included incising wooden boards, engraving on metal and metal inlaying on wooden boards.

Around 2900 BC the Egyptians started using papyrus sheet to write on. These were made from the Cyperus papyrus plant, a type of sedge considered to be holy as its flower represented the rays of the Sun god Ra, and its stem was triangular in shape – a symbol of eternal life for the Egyptian people. The green outer rind of the stalk was removed and the central part of the pith was cut into thin strips. Water was squeezed out of the strips with the help of a rolling pin to make it stronger and more flexible, and then soaked in water. For a lighter-toned sheet of papyrus, the strips were soaked for about 3 days, and for a darker sheet, they remained there for 6 days or so, causing the sugar present in the papyrus strips to ferment and give the desired darker brown colour. Once the soaking part was done, the strips were laid down on a cloth, arranged layer by layer with the next layer being perpendicular to the previous one. The sugar in the strips was enough for adhesion of the layers. Another cloth was put over it for absorbing the water, and then the whole thing was placed under a heavy rock or something. It was kept like that for 3 days and after that, sun dried for one more day. Thus, a sheet of papyrus was produced. Having said that, the procedure for making papyrus sheets was never recorded by the ancient Egyptians themselves, and it was kind of figured out by researchers through experimentation and by studying surviving samples.

The papyrus had a very smooth surface. The reed brush, ink and papyrus together provided a certain fluidity to writing. This resulted in the evolution of a simplified hieroglyphic script. Furthermore, two complete cursive scripts developed; chronologically – hieratic and demotic. Writing became a much more common practice among people. In simple words, these tools democratised writing.

Papyrus had become

one of the main exports of Egypt. It was introduced to Greece possibly by the Phoenician

traders. The Greeks also chose the humble reed to write on it. But this time, instead

of a brush-tip, the end of the reed was cut to a point and a slit was made at the

middle to draw the ink. This was what we now call a ‘reed pen’ (which was later

on also adopted by the Egyptians as well). They also wrote on parchment, wooden

board whitened with gypsum and another thing called wax tablet, made by filling

a hollowed-out wooden tablet with melted beeswax. The surface was scratched

with a metal stylus for writing and could be reused just by scraping off that layer

of wax with the help a spatula-like implement at the opposite end of the metal

stylus. The more ‘important’ writings were done on stones and metal plaques. In

the Roman Empire too, writing materials were almost the same and remained so

until the fall of the empire.

[To be continued…]

Very nicely written!

ReplyDeleteYou may add to this the writing practices of ancient China and Mesoamerica, where writing developed later but independently from Mesopotemia and ancient Egypt.

Also, another part can be dedicated to Indus script, which we have not been able to decipher till date; and the use of soapstone and terracota which were inspired by Mesopotemia and China respectively thus creating first globalised writing practices.

Thanks for your feedback

DeleteThe next part is exactly about that.

Remarkably Portrayed.

ReplyDeleteWaiting for the next part

~ Didivai

Very beautifully presented. Brief and crisp... Enjoyed reading. Waiting for the forthcoming parts.

ReplyDeleteThat's was absolutely great knowledge dor today's world, i got to know more information about history.... That was great job Antar... Keep doing.. i will keep reading.... 🌸🧿😉😉

ReplyDelete